History of Shinnai

Shamisen Music

Shamisen music, one of the traditional types of music in Japan, can be categorized into 15 genres. It originated in Osaka and has been passed down to the present, along with Bunraku puppetry and gidayu, both of which also originated in Osaka, in addition to Icchu bushi (from Kyoto), Bungo joururi (from Edo, that is, present-day Tokyo), naga’uta, ko’uta, ji’uta, ogi-e, utazawa, miyazono, and others.

Uta Mono and Katari Mono

The main types of shamisen music are uta mono (works that are sung) and katari mono (works that are narrated or chanted). Both forms are accompanied by shamisen music. The shamisen is a three-stringed instrument somewhat like a banjo.

Uta mono performers sing tales and describe scenes, whereas katari mono performers tell of people’s feelings. Joururi is a more dramatic and emotional form.

Uta mono include naga’uta, ji’uta, ko’uta, ha’uta and ogi-e.

Katari mono (also called joururi mono) include gidayu and the four styles of Edo joururi, which are shinnai, tokiwazu, tomimoto, and kiyomoto. Each style has its characteristic melodies, and uses different intonation and a different method of vocal production. Also, the shamisen are unique to each genre, differing, for example, in the size of the body and length of the neck, the thickness of the neck and the strings, and the thickness of the skin that covers the body. The text of the works performed also differ, depending on the performer’s genre.

The method and style of expression differ depending on the genre. Each has its own characteristic features. Within the style of each school, the performer’s individual mode of expression, together with the accompanying shamisen, creates a human drama using the beautiful Japanese text to communicate deep feelings, including both sadness and pleasure, weaving a dynamic, delicate, graceful, bold, intense, gentle, happy, and sad vocal line.

Shinnai Nagashi

When “shinnai” is referred to, many Japanese people think of shinnai nagashi. Shinnai nagashi is shamisen music that was played by strolling musicians. A man wearing a casual kimono and a special Edo-style head-covering (Yoshiwara kamuri) and a woman with her hair covered with a cotton cloth walked through the streets, especially in the geisha quarters, while playing the shamisen. When requested by customers, they performed in the street or in the customers’ houses. Up to around 30 years ago, such performers could be seen in Tokyo in places like Yoshiwara, Fukagawa, Yanagibashi, Asakusa, and Kagurazaka, but currently this Edo street tradition is no longer seen.

The work that the strolling performers played was an instrumental interlude from a famous shinnai work called Rancho. This style of outdoor advertising appeared at the end of the Edo period and continued until near the end of the Showa period.

Many Japanese people nowadays confuse the art of shinnai with shinnai nagashi.

Edo Joururi (Shinnai)

Edo joururi (shinnai) was a style of joururi that was created around 1760 by Tsuruga Wakasanojo I.

Miyako Hanchu, a student of Miyako Icchu the founder of Icchu bushi, moved from Kyoto to Edo (present-day Tokyo) in around 1730, and changed his name to Miyakoji Bungo. Later, he changed it again to Bungonojo. In Edo, he created the style called Bungo bushi. Its decadent and sensual melodies became all the rage in Edo.

In those days, lovers’ double suicides were prevalent in Edo. Perhaps because many of the Bungo bushi works appeared to glorify the romantic aspects of such double suicides, Bungo bushi was blamed for this social epidemic, and, in the interest of public health and safety, Bungo bushi was banned. For a while at least, it was forbidden to perform works in the Bungo bushi style. Even using the name was suppressed.

Lacking any livelihood, Miyako Bungonojo returned to Kyoto and gave up performing. However, his students, remaining in Edo, faced the problem that, having earned their livelihood by performing Bungo bushi, they were unable to continue to perform and had no source of income. So that they could continue as performers, they gave up their affiliation with Miyakoji and Bungo bushi, and each began to create his own style of music. The most prominent of these students were Tokiwazu, Tomimoto, Kiyomoto, and Wakasanojo. The new musical styles that they created came to be called the four schools of Edo joururi.

Although these four artists had had the same teacher, from this point, each of them embarked upon his own way. Tokiwazu and Kiyomoto collaborated with the actors and dancers of the kabuki theater, and changed their musical forms to adapt to the actors’ and dancers’ requirements. The Tomimoto style was less successful, and gradually disappeared. Wakasanojo did not collaborate with any other arts, and so his style of music, in the present day, most closely resembles the joururi of the Edo Period. Wakasanojo’s music developed in a form suitable for playing in ordinary rooms (rather than theaters). This is called zashiki joururi (zashiki being a tatami-matted room in a traditional Japanese house), or su joururi (plain joururi).

Tsuruga Wakasanojo I was a prolific composer, and many of his works continue to be performed in the 21st century.

Tsuruga Shinnai II, a blind performer, was a student of Tsuruga Wakasanojo I. His remarkably beautiful nasal tones and folksy way of narrating, which was said to have come from his special sense as a blind person, gained him great success. He was so popular that he would certainly be awarded a grand prize as the best musician if he were alive today. It was said that people all over Edo sang his melodies, imitating his voice. Tsuruga bushi came to be called shinnai bushi, after this performer’s name.

Shinnai created a different style of performing from other schools. This genre of narrative song was performed mainly in entertainment areas. It became more sensual and emotional than was characteristic of other styles, and it was very popular.

The traditional shinnai works that are performed currently have sophisticated melodic lines and enchanting stories. Shinnai’s melancholy atmosphere conveys the sadness of lovers’ double suicides. The shinnai shamisen, too, has a characteristic charm and beauty, with a delicate and elegant tone.

1.Music stand, 2.Fan, 3.Text, 4.Tea cup, 5.Chair

Genealogy of the Tsuruga School of Shinnai

I. Tsuruga Wakasanojo

In 1751, when Tsuruga Wakasanojo I was forced to give up performing Bungo bushi, he established Tsuruga bushi. He had been a native of Tsuruga, hence his name. As a child, he moved to Edo, where he was adopted by a samurai family. Later, he became a student of Miyakoji Kagadayu, who had been one of the master practitioners of Bungo bushi. Eventually, Wakasanojo struck out on his own. His compositions emphasized the distinctive narrative features of shinnai, but paid less attention to rhythm. He created melodies that had great emotional depth. Tsuruga Wakasanojo I was an outstanding singer-song writer, creating many masterpieces that are still performed. His most famous works include Wakagi no Adanagusa (Rancho), Akegarasu Yume Awayuki, and Ono’e Idahachi. He also made many arrangements of gidayu works in the shinnai style.

II. Tsuruga Tsurukichi

Daughter of the founder, Tsurukichi incorporated many elements from gidayu bushi and bungo bushi joururi into shinnai. She was a very talented woman who established shinnai as a novel style of joururi with complex melodies and fast tempo. Her most famous work is Sekitori Senryo Nobori.

III. Tsuruga Tsurukichi

Daughter of the second headmaster. One of her students was Tsuruga Hachidayu who, under the name Fujimatsu Rochu, revitalized shinnai which had been on the decline at the time.

IV. Tsuruga Shinnai

A blind shinnai performer, his beautiful nasal tones dominated the shinnai world. Due to his popularity, Tsuruga bushi came to be called shinnai.

V. Tsuruga Wakasadayu

The son-in-law of the third headmaster, he seems not to have been so talented. After his death in 1891, the Tsuruga direct lineage died out

VI. Tsuruga Shinnai

Suauki Shigetaro, the head of the famous Tsukiji fish market, took this name at the recommendation of his students. He became headmaster of the school in 1891.

VII. Tsuruga Shinnai

Son of the sixth headmaster.

VIII. Tsuruga Wakasanojo

Son of the seventh headmaster. He succeeded as head of the school at the age of eighteen, and took the name Tsuruga Wakasanojo. The reputation of his narrative style is still alive. He used a very elaborate and delicate melody and exquisite lyrics.

IX. Tsuruga Wakasadayu

He was the leader of the school and became head of the school on the recommendation of his students. His former name was Tsuruga Shigedayu. He passed away in 1988.

X. Tsuruga Wakasa

Son of the ninth headmaster. He was the first shamisen player to become head of the school. He died in June of 1999.

XI. Tsuruga Wakasanojo

The eleventh headmaster.

At Akagi Shrine in Kagurazaka

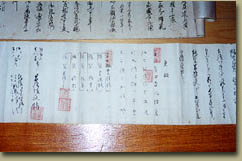

(right) Hanging scroll written by Tsuruga Wakasanojo I in approximately 1737. Words of advice for new students.

“Modern people do not understand the musical virtue of nature. All new students of this school must learn from the beauties of nature and practice diligently.”